لنتفق أولاً على أن المكان في فلسطين – ولا أقول المكان الفلسطيني – بالنسبة إلى اللاجئين في خارجها، لم يُبنَ من الخارج، وإنما ورثناه من حَمَلته الخارجين منه، ثم أضفنا عليه تعديلاتنا؛ فبنَينا وما زلنا نبني. ففي المنفى الأوروبي مثلاً، لدينا كفلسطينيين، مكان مميز هو فلسطين أُخرى موازية.

بالنسبة إليّ، كلاجىء فلسطيني في أوروبا، كثيراً ما كنت أغرق في الاشتغال على عملية البناء تلك، حين وصلتني دعوة المتحف الفلسطيني إلى إلقاء مداخلة بعنوان: “بناء المكان من الخارج”، وكنت حينها قد وضعت حجراً على شكل رواية بعنوان “تذكرتان إلى صفورية”، وفوقه حجر مماثل آخر بعنوان “سيناريو”، وبعدهما “عين الديك”، حجر ثالث شكّل طبقة ثالثة لجيل ثالث، فوق بيت أبي في المخيم، اللاجىء الثاني الذي بنى بيته فوق بيت جدّي، اللاجىء الأول.

المختلف هنا أنني أبني مكاني الفلسطيني، بالكلمات، بالأدب، وليس بالحجارة والأسمنت، بعدما حلّت نكبة ثانية بنا، نحن فلسطينيي سورية؛ نكبة أحالت المادي والحجري، مرة أُخرى، إلى معنوي، وحوّلت الحجارة إلى كلمات، وثبّتت مكاننا الأوروبي، المعنوي منه والمادي، وهو المكان الذي ما زلت أكوّن فيه، بكلمات أدبية تكون نقدية في بعض الأحيان، مادته الأساسية التي هي الذكريات والخيال، وهي مواد غير ملموسة. كما أن المكان – ولا أقول متى ينتهي بناؤه، فالأمكنة في الأدب لا ينتهي بناؤها، والأمكنة في الخيال لا تستقر، والأمكنة في الرغبات تتهدم متى اقتربت من انتهاء ما – سيكون، أو لأكون دقيقاً: فلسطين ستكون، باشتغالي هذا، مكاناً من كلمات، فالوطن – من دون شعارات لأنها واقعية تامة للمنفيّ – يكون في الأدب.

لا أقول ذلك كهارب من مواجهة مع مكان مادي هو موجود فعلاً، ضمن خطوط طول وعرض، ولا أقول ذلك للتهرب من سؤال صار مملاً لكثرة ما سمعته: “هل تظن فعلاً أن فلسطين الآن، إن زرتَها، ستكون كما تحب؟!” يتلفّظه سائله مستنكراً عليّ رغباتي وخيالاتي وفلسطيني، متشاطراً، بارزاً تفوّقه عليّ كعارف حقيقي بفلسطين المادية التي أعرف وهمَها فقط، أو حضورها الموازي فقط. لا أقول ذلك إلّا لأن هنالك فلسطين واحدة أعرفها، ورثتُها وبنَيتُ على ما ورثته، ولا أقول أني حطمت ما ورثته، فالرغبات المراهقة والمفتعلة غالباً، في التحطيم المعنوي للمتوارَث، نجت منها، لحسن حظي، حكاياتُ جدّي عن ترشيحا التي يعرفها. هنالك إذاً فلسطين، واحدة وأعرفها، ورثتها وأسستُ على ما ورثته من تلك الحكايات رغبتي في أن أبني عليها مكاني المرغوب فيه.

روح جدّي، أبو محمود، حائمة في الرواية الأولى، وحاضرة في ذهن حفيده، يوسف، الذي يتحضر للعودة إلى صفورية بجواز سفر فرنسي، يتنازعه قلق إزاء أن تكون البلد غريبة عنه، أو أن يكون هو غريباً عنها، متى وصلها وتمشّى في شوارعها، فلا يكون كأهلها، ولا تكون البلد بلده. روح جدّي حاضرة في الرواية الثانية، في تساؤل حفيده، كريم، عن سبب خروجه ولجوئه إلى حيفا. تساؤل فيه لوم وألم وعذر صغير، وقلق تجاه فكرة العودة التي لا يعرف كريم إن أرادها إلى حيفا المدينة في فلسطين، أم إلى حيفا المخيم في سورية، فحيفا الأولى التي كانت دوماً مستحيلة لحقتْها الأشد استحالةً. وفي الرواية الثالثة يسائل سمير كل ما كان ألّفه وألِفه: هل يكتفي بفلسطين في بيته وحيّه ومدينته باريس؟ تساءلت مستحضراً جدّي لأكتب له حكايتي في الشتات لتفادي كتابة حكايته هو في المخيم.

المكان الفلسطيني هو حيث كان جدّي أبو محمود الذي حملت مع اسمه ذكرياته وحكاياته وتأثّره بها كلما حكى عن ترشيحا في أعوامه الأخيرة، وقد استوعب أن لا عودة بعد الخروج. المكان تأسس بصوته المبحوح، وخيالاتي عن المكان بُنيت على ذلك الصوت. لا أقول أني أعرف قريتي شارعاً شارعاً، بيتاً بيتاً، مثلما ربما يعرفها أهلها الساكنون فيها، بل أعرف صوتها، كما يعرفون هم رائحتها. لا أقول أني أعرف المكان المادي، بل المكان المعنوي المبني على الصوت، فالذكريات التي نقلها الصوت لحقت بها الخيالات واحتوتها.

لذلك، لا أرى فلسطين التي أعرفها – وما زلت في طور التعرّف إليها ما دام هنالك خيالات وذكريات ورغبات – ولا أراها خارجة عن المكان. فهي المكان لديّ، إذ لا فلسطين أشد موثوقية من تلك التي حكاها لي جدّي، والتي أسستُ حكايات على حكاياته. هذا هو المكان، هذه هي فلسطين، أو هذه هي فلسطين عندي، بعدما كانت فلسطينُ فلسطينَ في الرواية الأولى، وبعدما صارت فلسطينُ المخيمَ في الثانية، ثم صارت فضاء أليفاً في الثالثة. فبعدما كانت المكان المبتدأ في الأولى، القرية، وبعدما صارت المكان الموقت في الثانية، المخيم، استحالت فلسطين إلى اللامكان في الثالثة، وصارت الأمكنة كافة.

فلسطين الآن هي نُتَف حكايات أبو محمود الذي ترك أهله في ترشيحا وخرج بعدما لاحقه الصهيونيون هو ورفاقه من الفلاحين الذين قاتلوا ببنادق ساذجة، خرج وهو يعرف أنه مطلوب بالاسم، وأنه لن يعود ما دامت إسرائيل هناك، ولهذا لم يأخذ معه مفتاحاً، ولم يتوهم بعودة قريبة، وإنما ابتعد في القطار إلى المحطة الأخيرة، إلى المخيم الأبعد، في حلب.

أقول ذلك لأجيب لنفسي عن سؤالي الذي لم أستطع كبت صراخي به كتابةً: لكن لماذا خرجتَ من البلد؟ لا أجد نفسي سوى حائم، بعبثية لا تنتهي، بين السؤال والإجابة:

– لماذا خرجتَ من البلد؟

– كنتُ ملاحقاً.

– لكن لماذا خرجتَ من البلد؟

– كنتُ سأُعدَم.

– لكن لماذا خرجتَ من البلد؟

– لو لم أخرج ما كنتَ ستكون.

أكون هنا، خارج البلد، بانياً إياه مع جدّي، من الأول، من النكبة، من الخروج من القرية، الخروج الأول، الخروج من المكان الأول، بناءً على بناء، إلى الخروج الثاني، خروج أبي من المخيم، من بركة الوحل القذرة إلى بركة النفط العفنة، فالخروج بثلاثة أضعاف عن المكان الأول، خروجي أنا، إلى البحر الأوروبي بزرقته الأشد إقلاقاً من البركتين الغامقتين.

المكان الفلسطيني يُبنى في ذهني في هذه الأمكنة الثلاثة، المخيم والمدينة والقارة؛ يُبنى لا ليكون صورة عن فلسطين موثّقة بكلام لساكن في تلك البلد بأني “أعرف فلسطين أكثر من غيري.” قد أكون أو لا أكون أعرف فلسطينَه، المكان المادي، لكني أعرف جيداً فلسطيني أنا، المكان المعنوي الذي أسستُه بحكايات وذكريات وخيالات ورغبات، وهذه هي التي أسكنها.

وحين أعود يوماً إلى فلسطين التي لا أعرفها، أو حين أزورها، سأكون رؤوفاً فلا أطالبها بأن تحاول التخفف من حمل التاريخ، أو التماثل مع فلسطين التي أعرفها. أعرف استحالة ذلك، فكل واحدة لها عالمها، ومتى أدخل واحدة أكون قد خرجت من الأُخرى.

حتى اللحظة، لا أعرف سوى الأُخرى، فلسطينُ الأُخرى التي بنيتُها. أمّا المكانُ الآخر فهو مكاني، وأنا كذلك، سأبقى دائماً ذلك الآخر لدى فلسطين التي تعرفونها.

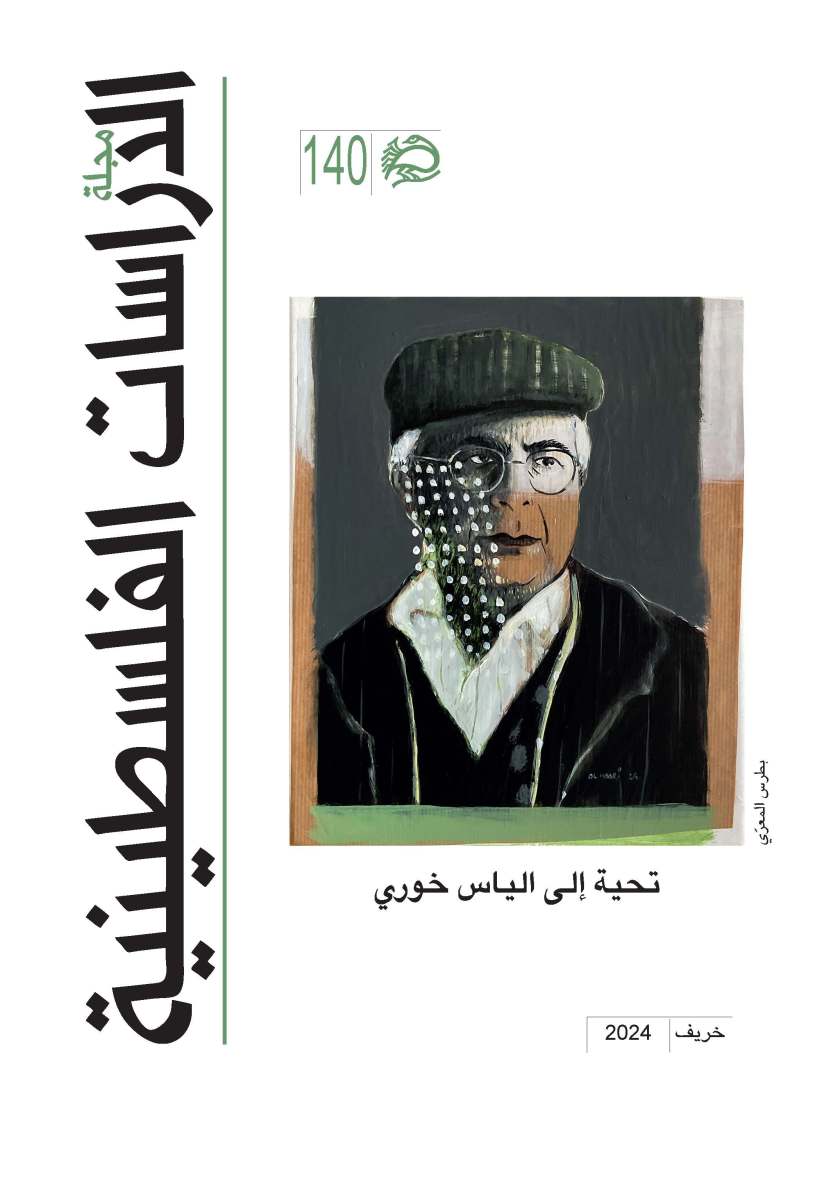

* نُشرت هذه المادة في مجلة الدراسات الفلسطينية، العدد 140. بالتنسيق مع المتحف الفلسطيني.

Let us first agree that the place in Palestine – and not specifically the Palestinian place – for refugees abroad was not built from the outside. Rather, we inherited it from those who left it, and then made changes ourselves; we built on it and continue to build. For example, as Palestinians in European exile, we have a unique place, a parallel Palestine.

For my part, as a Palestinian refugee in Europe, I was often absorbed in this process of construction when I was invited by the Palestinian Museum to give a lecture entitled “Building a Place from the Outside”. By this time, I had already laid a foundation stone in the form of my novel, Two Tickets to Saffuriya, then a second, entitled Scenario, and still a third stone, Ain al-Dik, constituting a third layer for a third generation, living above my father’s house in the camp. He, my father – the second generation refugee – had built his house above that of my grandfather, the original refugee.

What’s different here is that I’m building my Palestinian space with words, with literature, and not with stones and cement, after a second Nakba struck us Palestinians in Syria; a catastrophe that turned material and stone, once again, into spiritual matter, that turned stones into words and fixed our European place, both symbolic and physical. It’s a place which I continue to build with literary, sometimes critical words – intangible materials, memory and imagination. This place – and I don’t specify when its construction will be completed, for places in literature are never finished; those imagined are never stable, and those desired disintegrate as soon as they seem to be almost fully realised – will be, or more precisely, Palestine will be a space of words, thanks to my work. For the homeland – without slogans, just the reality of exile – can exist through literature.

I say this not to avoid a confrontation with a physical place that does actually exist, with its latitude and longitude, nor to evade a question that has become tiresome through repetition: “Do you really think that today’s Palestine, were you to visit, would be as you imagine?” Whoever asks this question often does so by denouncing my desires, my dreams, and my Palestine, displaying his superiority as a true connoisseur of the physical Palestine of which I know only the shadow, or parallel existence. I say this only because there is only one Palestine I know, inherited and built on what I inherited, never destroying that legacy. Fortunately, my grandfather’s tales of Tarshiha, which he knew so well, preserved my heritage from the often artificial adolescent impulses of destruction. I only know one, the one I inherited and on which I have based my desire to build my dream space.

The spirit of my grandfather, Abu Mahmoud, floats through the first novel and accompanies his grandson, Youssef, as he prepares to return to Saffuriya on a French passport. He is torn by anxiety that the country will seem foreign to him, or that he himself will be a stranger there, as he walks its streets, feeling neither like its inhabitants nor at home. The spirit of my grandfather is also present in the second novel, in the questions of his grandson, Karim, who wonders about the reasons for his departure and exile to Haifa. Karim’s questions are a mixture of reproach, pain, a hint of forgiveness, and worry about the idea of returning: he doesn’t know whether he wants to return to Haifa, the city in Palestine, or to Haifa, the camp in Syria. The first Haifa, still an impossibility, was followed by the one that is even more inaccessible. In the third novel, Samir questions everything he has built and known: can he be content with Palestine in his home, his neighbourhood and his city, Paris? In evoking my grandfather, I questioned myself, writing my story in the diaspora to avoid rewriting his in the camp.

The Palestinian place is where my grandfather, Abu Mahmoud, was, and I carried his memories and stories with his name, touched by the emotion he showed every time he spoke of Tarshiha in his last years, understanding that there would be no return from exile. This place was established by his voice, and my representations of it were built on that voice. I don’t pretend to know my village street by street, house by house, as its inhabitants might, but I do know its voice, just as they know its smell. I’m not saying that I know the physical place, but rather the immaterial place based on the voice, because the memories transmitted by this voice have been enriched and enveloped by the imagination.

Thus, I don’t see the Palestine I know – and I continue to discover it as long as memories, dreams and desires exist – as being outside space. There is no more reliable Palestine than the one my grandfather described, and I have built stories from his. This is the place, this is Palestine, or rather, this is my Palestine: after Palestine was simply “Palestine” in the first novel, and became “the camp” in the second, it became a familiar space in the third. It was initially the place of origin in the first novel, the village, then the temporary place in the second, the camp, before turning into a “non-place” in the third, where all places became possible.

Palestine is now made up of fragments of the stories of Abu Mahmoud, who left his family in Tarshiha and left after being pursued by the Zionists, he and his fellow peasants fighting with rudimentary rifles. He left knowing that he was a wanted man, and that he would not return as long as Israel existed. He took no key with him, nor imagined a return anytime soon; he boarded the train to the last station, to the farthest camp, in Aleppo.

I say this to answer the question I couldn’t hold back, which resonates in me insistently: Why did you leave the country? Here I am in an absurd oscillation between question and answer:

– Why did you leave the country?

– I was being pursued.

– But why did you leave the country?

– I was going to be executed.

– But why did you leave the country?

– If I hadn’t, you wouldn’t be here.

I’m here, outside the country, rebuilding it with my grandfather, from the very beginning, from the Nakba, from the first exodus from the village, the original exit from the original place, construction after construction, to the second exodus, that of my father, leaving the camp, passing from the dirty mud pool to the nauseating oil one, and finally my own triple exodus from the place of origin, to the European sea, whose blue is even more disturbing than the two dark pools.

The Palestinian place is constructed in my mind through these three spaces: the camp, the city and the continent; it is not a simple image of Palestine documented by the words of a local saying, “I know Palestine better than anyone.” I may or may not know this Palestine, the physical place, but I do know my own Palestine, this symbolic place I’ve constructed with stories, memories, dreams and desires – and this is the Palestine I inhabit.

The day I return to Palestine, the one I don’t know, or the day I visit it, I will be indulgent and not ask it to lighten the weight of history or align itself with the Palestine I do know. I know that’s impossible: each has its own world, and every time I enter one, I leave the other.

For now, I only know the other, the Palestine I have built. This other place is mine, and I will always remain this other in the face of the Palestine you know.

The text originally appeared in Arabic in the autumn issue (140) of Majallat al-Dirasat al-Filastiniyya.